|

| Mike Dunlap and his 1-1-3 matchup zone will bring a new brand of basketball to the Lions |

If there was one coaching hire that probably didn't get as much praise as it should, it had to be LMU's decision to hire Mike Dunlap. While the early nature of the hire (they literally hired Dunlap a day after they decided not to renew Max Good's contract; though to be truthful, Good was dead-man walking from the middle of the WCC season on) probably hurt publicity (didn't stick out among all the other "bigger hires"), Dunlap's hire could be an under-the-radar move that could provide a spark for a program that has failed to get much going since their Paul Westhead "Run and Gun" days.

First off, Dunlap's pedigree is impressive, though I think his recent NBA stint with Charlotte unfortunately is what lingers on the minds of the most common basketball fan. Yes, the Bobcats were not good in 2012-2013 as they finished 21-61 and last in SRS and defensive rating (-9.29 and 111.5, respectively) and second-to-last in offensive rating (101.5). Yes, he was fired after only one season, and the Bobcats significantly improved this year in his absence (they went 43-39 and made the playoffs for only the second time in franchise history). But coaching in the NBA is a difficult tight-rope to walk. We have seen all the time coaches find success in the NBA only to fail in college and vice versa. Sure, there are success stories of coaches who managed to do both (Larry Brown for example), but evidence shows that some coaches are meant for the college or the professional game and not necessarily both.

Dunlap falls into the latter category because he is at the heart a "program builder". While critics of the hire point to Dunlap's failings in the NBA, they fail to recognize his immense success with Metro State, a commuter school in Denver that has no football team in the Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference. At Metro State, Dunlap tallied a 248-50 record with two Division II national championships, and four DII Final Four appearances. Those kinds of numbers at any level are incredible, and to do it with challenging circumstances (less recruiting budget, less tradition and fan fare in a primarily pro sport metro area) only makes it more impressive. As evidenced by Mark Few at Gonzaga and Randy Bennett at St. Mary's (and to some extent Rex Walters at USF), in order to be a successful program in the WCC, a coach needs to be in it for the long haul and really build things from the ground up. Dunlap has done that before with Metro State and with even lesser resources than what Few and Bennett had when they came into their positions.

In addition to being a "program builder", Dunlap brings in an identity as a defensive-oriented coach, something that is quite antagonistic with the history of LMU basketball. Since the days of Westhead, the Lions have been known for offense and points, and that is something LMU fans have come to expect to varying levels of success. If there was a positive of the Good-era at LMU, it was that he brought in talented players who could light it up on the offensive end. Anthony Ireland and Drew Viney were Good recruits who excelled as offensive-oriented players who could entertain fans and put points on the board. Good's teams ranked in the top-200 in adjusted offensive efficiency according to KenPom.com 4 out of his 6 years, and ranked in the top-120 in tempo in 4 out of 6 years as well (including Top-50 in 2010 and last season). Good wanted his Lions to play fast, play loose and focus on putting the ball in the basket. In an offensive-oriented conference, his philosophy seemed pretty in-line with many other programs in the WCC (the conference ranked 6th in offensive efficiency last season).

But being similar doesn't always bode well for success. Good only produced two winning seasons (2010 and 2012) in his time at LMU and while injuries did ravage his Lions throughout his career, his teams' struggles on defense always compounded things as well. Good's teams ranked in the Top-150 in defensive efficiency only twice in his career (2012 and 2013), and last year, despite a promising start which included an upset of BYU at home, the Lions struggled on the defensive end, finishing with an adjusted defensive rating of 112.4 in conference (9th) and 106.3 for the overall year (202nd in the nation). Good's teams may have been entertaining at times and showed flashes of brilliance (their win against BYU last season in Los Angeles was a thing of beauty), but it was obvious that the team needed a new philosophy and fresh face to help turn things around for a once proud program. (Seriously, how many WCC schools have 30 for 30's that feature them?)

Dunlap at the very least brings something different. His most recent college experience was at St. John's where he served as an assistant for the Red Storm under Steve Lavin. Dunlap found success as somewhat of a defensive coordinator for Lavin, much in the vein of Tom Thibodeau for Doc Rivers during the Boston Celtics' 2008 title campaign. With Dunlap's expertise, the Red Storm primarily applied a 1-1-3 matchup zone, a defense that he developed from his days as an assistant at Arizona (Dunlap was an assistant in 2008-2009), where Lute Olson regularly employed the defense with his athletic guards. The 1-1-3 matchup zone basically is a combo defense that takes the 2-3 zone and meshes it with some man-to-man principles. The result is a defense that allows teams to keep the "zone defense" identity that they wish, while at the same time allowing them to apply more pressure on defense without switching completely (most zone defenses struggle to create turnovers). The defense also has to potential to create a "junk defense" effect, as it confuses defenses and contains teams that heavily rely on one perimeter player that creates most of the offense.

At St. John's, the Red Storm found success on the defensive end employing Dunlap's 1-1-3 approach, especially in the 2010-2011 season. That year, the Red Storm ranked 45th in the nation in adjusted defensive rating at 95.2, and had a steal percentage of 12.3, 26th best in the nation. The result was a 21-12 record and their first NCAA Tournament since the Mike Jarvis days (shout out to Ron Artest and Erick Barkley!) despite playing one of the toughest schedules in the nation (10th hardest according to Ken Pom).

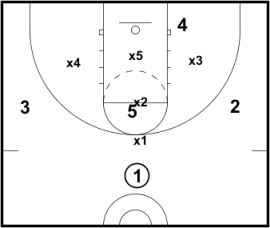

So how does the 1-1-3 matchup zone work? Here is basic look at how the defense initially sets:

As you can see, the defense looks like a 2-3 zone below the free throw line, but things get different once the ball swings to the perimeter to one of the wings. Let's say the point guard passes it to the right wing to the 2 man. Here's is how the defense rotates:

This isn't a "Box and 1" where the 1 stays on the opposing 1. Instead, the 1 sags to the free throw line on the left elbow on the pass to the wing (to take away skip pass opportunities), and the two and three swarm to pressure the opposing two. In many ways, that is one of the benefits of the 1-1-3: it causes a lot of pressure on the offense with double-teams and traps (characteristic of pressure man-to-man defenses), while preventing penetration and easy passes in the post (characteristic of traditional zone defenses).

In 2011 early in the season with Dunlap still on staff, the Red Storm played Arizona in the 2K Sports Classic at Madison Square Garden (pretty much a home game for the Red Storm). Let's see how the first possession played out as they employed their 1-1-3 zone defense

As you can see, the Red Storm are in their 1-1-3 set while Arizona is in a 4-out set themselves. The guard on the opposite end is on the wing, while two guys are taking away the post. Let's see how the defense reacts when the ball is swung over to the other side.

As the ball is swung to the post player, the zone forces him into the corner, which for him is not a high-percentage shot and out of his comfort zone. The defense is looking to trap, and they are taking away the pass into the middle at the free throw line as well. Because of the angle, the skip pass would be difficult as well, and thus, the only option for the Wildcat post player is to shoot the jump shot or pass it back out to the wing (which he does).

After a couple of passes, the ball comes back to the same player, who pretty much receives the ball in the same position. This time he has a 1-on-1 matchup, and feels comfortable with the shot. That being said, the athleticism of the defender (the 1-1-3 succeeds with athletic players, not necessarily size) catches no. 14 for Arizona by surprise.

The Red Storm get him to shoot this time, and not only is he forced to take a difficult shot, but it is blocked as well. Furthermore, there is nobody in the post when he takes the shot. Arizona is backed out to the perimeter, and though they crash and get the rebound, it does set the Red Storm up well for the rebounding position (lack of size hurt the Red Storm in rebounding, as they finished 342nd in the nation in offensive rebounds allowed percentage that year). On the same position after getting the rebound, the Wildcats try to set it up on the other side and look to get a better shot to their player in the block.

If you're an Arizona fan, this looks like a better scenario. The post player is in the block and looks open as well. The wing player shot fakes and looks to pass it down to that seemingly open player. But the benefit of the 1-1-3 is that it is established on pressure and producing turnovers, and to do that, the players need to be ready to swarm and entice passes to which they can get the steal or force the turnover. That is the case here: no. 4 (player in the middle of the key for St. John's) is giving the look that he is fronting 44 for Arizona in the post. But, by feigning this coverage, he is setting up to pounce on the Arizona post player who thinks he is going to have a high percentage shot when in reality, he is going to be jumped on by the Red Storm defense. Which results in...

no. 4 for St. John's pouncing on the player, denying and batting the ball off the Arizona player and out of bounds for the turnover. And just on that first possession, the Red Storm, through their 1-1-3 matchup zone are proving to the Wildcats that shots aren't going to come easy, and that the Red Storm not only have speed on the perimeter on defense, but in the post as well (to make up for their lack of size).

Dunlap is an interesting character for sure. In the year off of coaching, he maintained a blog and is well known for his appearances in coaching videos promoting his 1-1-3 matchup zone as well as writing articles on general coaching philosophy (in his 10 keys to practice, he advocates the use of clear water bottles so he knows how much water his players are drinking in practice). But, he has found success with the 1-1-3, especially at St. John's, as it caused turnovers and made up for teams that traditionally lacked size and depth (both problems the staff dealt with in his two seasons with the Red Storm). The same problems are most likely going to be true at LMU: he is going to have a tough time recruiting elite size to a WCC school (most WCC teams do), and it is going to take him a while to develop any depth with his roster (Good was around average as a coach when it came to bench minutes percentage, hovering around 30-32 percent in terms of bench minutes). His 1-1-3 philosophy on the defensive end will take advantage of the players that have traditionally come through the Lions program (usually smaller, but athletic players), while also conserving their energy and getting maximum efficiency from them, especially on the defensive end.

It is going to be interesting to see the progression of the Lions under Dunlap. Traditionally, coaches have been more offensive-oriented in their time at LMU and focused on pushing the pace, not surprising considering that was the most exciting and successful basketball played at LMU. But, a more-defensive approach could be the shot in the arm this Lions program needs. It never really seemed to be a strength of Good's, and this kind of style would be a change of pace that could be a competitive advantage in a conference where most teams were average or below when it came to defensive efficiency (only Gonzaga and San Diego bucked this trend last season, and Gonzaga was flat out dominant thanks to Przemek Karnowski in the paint). While Westhead was available and would have been the most glamorous hire, Dunlap and his pedigree will help provide a distinct identity to this Lions program and could get them on their way to becoming a more legitimate squad in a WCC that is rising in terms of popularity as well as competitiveness.

No comments:

Post a Comment